"On Time Delivery" highlights sled dog mail delivery

By Melody Parker, NPM Intern

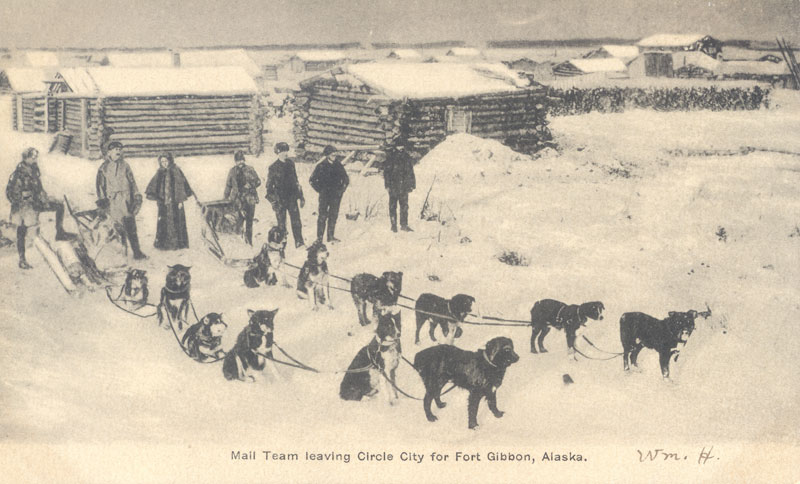

Many visitors to the National Postal Museum see our Alaskan dog sled, used by mail carriers Ed and Charlie Biederman in the 1920s and 30s. The delicate-looking, hand built sled is made of hickory, with iron runners, moose hide lashings and cotton cords that secured the loads of mail that were delivered on a 160-mile route between Circle and Eagle, Alaska.

The dog sled’s fragile and empty appearance makes you wonder what did it carry? Why was it important? A sled like this is “one of the small reminders of a whole system of transportation and communication,” says William Schneider, author of On Time Delivery: Dog Team Mail Carriers, a book chronicling sled dog mail transportation that will be released in April 2012.

Schneider, an anthropologist who moved to Alaska in the 1970s to pursue research interests with Alaska Natives, took an interest in dog team mail carriers after hearing stories about them and traveling a few of the remaining dog trails. The story was nearly untold, which prompted him to probe deeper into this era of a greater connection to the land before the stories of these men and dogs faded from history.

For a period lasting about forty years until the 1940s, dog team mail carriers were charged with carrying mail and maintaining overland trails in interior Alaska as both postal employees and Star Route contractors. On Time Delivery recounts this unique mail service, while preserving the personal stories of the men who delivered the mail by sled dog teams and the communities that supported them.

On Time Delivery: There was little need for mail service in Alaska prior to the gold rushes of the late 1800s and early 1900s when prospectors flocked to the interior. The newcomers, unlike most longtime Alaskan residents, were highly literate, wrote letters, and demanded regular mail service as a way to connect to their friends, family and business partners back home. Mail is an important part of the family history of Alaskans who can track their ancestors back to the Gold Rush era.

Sled dog mail carriers negotiated steep snowy summits, treacherous terrain, wind and even wildlife—like ornery moose—as they traveled the trails between mail cabins and roadhouses to deliver letters to their destinations. If conditions were good and mail loads were light, a carrier could travel between 20 to 30 miles in a day.

Carriers’ families were often involved behind the scenes, too. One mail carrier’s wife took care of their nine children while her spouse ran the mail. “She made clothing for the family, sewed dog booties, and helped with fishing in the summer,” Schneider notes in his book.

On Time Delivery echoes the way mail carriers viewed their work—it was not a sensational story, but part of their everyday lives. “That’s not to say that the job wasn’t dangerous by any standard,” writes Schneider, who included a remarkable anecdote about a carrier who fell through thin ice and was pulled out by his dogs, yet continued on to the end of his route with blistered and frostbitten feet.

Learn more about dog sled mail carriers

Deep impact: Mail transportation after the turn of the 20th century deeply affected the culture of the Alaskan community, from how people moved around and met each other, to exposure of natives to the outside world via newspapers and magazines, to boosting literacy.

With the transition to airmail from sled dog mail service, the traditions and trails were abandoned but for the modern Iditarod, Yukon Quest, and Percy DeWolfe Races, that pay homage to a generation of rural Alaskans who experienced the country in a different way than anyone will ever again. Today, bush planes deliver most mail to remote Alaskan residents.

About the dogs: Mail carrying sled dogs were much larger than the dogs we see in the Iditarod races today. They weighed about 75 to 100 pounds, with thick coats of fur to keep them warm during temperatures as low as 50 to 60 degrees below zero. The dogs wore handmade booties to protect their feet, and they were fueled by dried fish that they ate along the trail. They were durably built, but not for speed like the thinner-coated racing sled dogs we see today.

In the old days, sled dog mushing was a common form of transportation to villages and towns. Today, people come to town by air or connect to the road system via snowmachines. Schneider is a “backyard musher” who enjoys sled dogs for recreational purposes rather than for racing. He cares for six dogs—that’s a lot of dog food, but not nearly as much as his brother-in-law uses to feed his 30 racing dogs.

About Mr. Schneider: William Schneider lives with his wife Sidney and daughter Willa a few miles from the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. He is the editor of many books and also the author of So They Understand: Cultural Issues in Oral History.