The Anthrax Mail Attack: Postal Workers on the Front Line

By Nancy Pope, Historian

This is the second in a series of three posts addressing the anthrax bioterrorism attacks that took place in October 2001. Click for parts one and three.

On October 15, 2001, an aide to then-Majority Leader Senator Tom Daschle of South Dakota opened an envelope containing a threatening message and powdery substance that was later determined to be anthrax. The senators’ letters each contained the following note:

09-11-01

YOU CAN NOT STOP US.

WE HAVE THIS ANTHRAX.

YOU DIE NOW.

ARE YOU AFRAID?

DEATH TO AMERICA.

DEATH TO ISRAEL.

ALLAH IS GREAT.

The Senator’s staff was quickly provided with antibiotics. Twelve Senate offices shut down the next day, the Capitol the day after.

During this time, postal workers continued to process the nation’s mail, including those in the Hamilton Township facility in New Jersey and the Brentwood facility in Washington, D.C. Two letters, addressed to Senators Patrick Leahy of Vermont and Daschle, carrying the fictional return address of: “4th Grade / Greendale School / Franklin Park NJ 08852” had entered the mail stream in New Jersey. They passed through the Hamilton Township facility in New Jersey, and later the Brentwood facility in Washington. Daschle’s letter had traveled to the Capitol from Brentwood while Leahy’s letter was sidetracked to the State Department after a computer eye misread the letter’s ZIP code from 20510 for 20520.

The day after the Capitol shut down a Hamilton postal worker tested positive for cutaneous (skin contact) anthrax. A second worker from the same facility tested positive the next day. Meanwhile, at Washington, D.C.’s Brentwood postal facility, just over a mile north of this museum, postal workers continued work as usual. Senior postal officials continued to be assured by Centers for Disease Control experts that the envelopes carrying anthrax would not be a danger to postal workers.

The Hamilton facility closed for testing on October 18. The Brentwood facility remained open and operational. In the meantime, some of the Washington postal workers had begun seeking medical treatment for virus-like symptoms. One was Thomas Morris Jr., a distribution clerk in the Brentwood facility. His symptoms began on October 17, but were considered the result of a simple virus. In the early morning hours of the next Sunday Morris called 911 to report his breathing was “very, very labored.” Morris continued to explain what he feared might be the cause:

MORRIS: "Ah, I, I don't know if I have been, but I suspect that I might have been exposed to anthrax."

OPERATOR: "Do you know when?"

MORRIS: "It was last, what, last Saturday a week ago, last Saturday morning at work. I work for the Postal Service. I've been to the doctor. Ah, I went to the doctor Thursday, he took a culture, but he never got back to me with the results. I guess there was some hang-up over the weekend, I'm not sure. But in the meantime, I went through a achiness and head achiness, this started Tuesday. Now I'm having difficulty breathing and just to move any distance, I feel like I'm going to pass out. I'm here at the house, my wife is here, I'm on the couch." (1)

Morris arrived by ambulance at the hospital but died only a few hours later from anthrax inhalation. The same Sunday morning a second Brentwood postal worker, Joseph Curseen, was taken into a local hospital emergency room with flu-like symptoms. Curseen was sent home where his symptoms worsened, and he returned to the hospital. He died six hours after his second arrival, also from anthrax inhalation.

The nation’s focus turned from the US Capitol, which reopened on October 22, to the postal facilities and their stricken workers. In spite of prevailing expert opinion, it had become crystal clear that anthrax spores not only could escape from envelopes, but in fact had done so in alarming numbers. The other seven postal workers who were infected with anthrax and survived worked in either the Hamilton or Brentwood postal facility. Brentwood was closed on October 21.

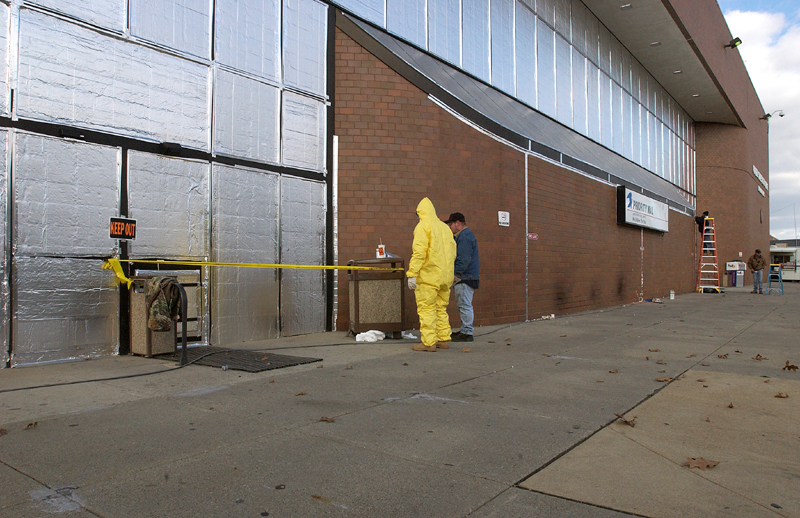

The Brentwood facility reopened after a cleaning and decontamination process that cost $130 million. The Hamilton postal facility reopened in March 2005 at the cost of $65 million.

In recognition of the deaths of Brentwood’s postal workers, the facility was official renamed Curseen-Morris. On February 19, 2010, the FBI and US Postal Inspection Service announced that the investigation of the anthrax letters had been concluded, with evidence pointing to Dr. Bruce Ivins, a government scientist, as the culprit. Ivins, aware of the government’s suspicions, had committed suicide in July 2008.

(1) Internet news site, ABC News, accessed September 29, 2011, (abcnews.go.com/US/story?id=92222&page=1)

About the Author

The late Nancy A. Pope, a Smithsonian Institution curator and founding historian of the National Postal Museum, worked with the items in this collection since joining the Smithsonian Institution in 1984. In 1993 she curated the opening exhibitions for the National Postal Museum. Since then, she curated several additional exhibitions. Nancy led the project team that built the National Postal Museum's first website in 2002. She also created the museum's earliest social media presence in 2007.