Untold Stories: African American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality

By guest blogger Philip F. Rubio

On November 7, 1940, just two days after the election that President Franklin D. Roosevelt won for his third term, he signed Executive Order 8587 abolishing the civil service application photograph. This was no minor matter. The NAACP and the historically-black National Alliance of Postal Employees (NAPE, formed in 1913 after blacks were excluded from the Railway Mail Association) had been campaigning against the use of the application photograph since the Wilson administration began using it in 1914 to screen out as many African American applicants as it could. And the National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC), at the time still battling to keep Jim Crow branches out of its organization, had voted at its 1939 convention to support abolition of the discriminatory application photograph.

Roosevelt’s order produced no media coverage—except in the black press, which I relied on for much of my research into the history of black postal workers and their activism. The black press hailed it as a victory. Indeed, African American postal employment grew dramatically as a result of that order, the World War II labor shortage, and Executive Order 8802 banning government and defense industry discrimination in 1941. It seems fitting that I will be speaking and showing slides based on my book There’s Always Work at the Post Office: African American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality at the National Postal Museum on the day before the 70th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 8587. But that order, the application photograph, Jim Crow postal unions, and black-led campaigns for equality at the post office and its unions—among many other things—were all unknown to me during my twenty years that I worked for the United States Postal Service.

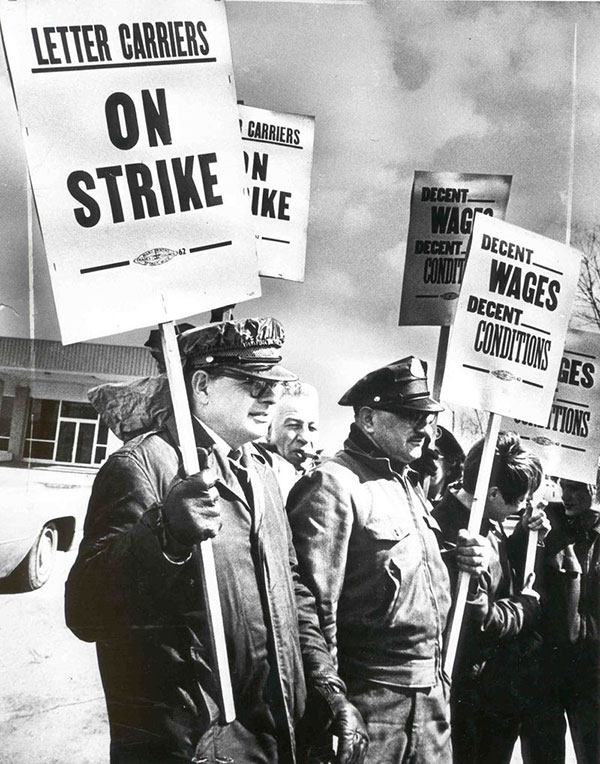

While working at the post office in North Carolina I became more aware of the historical narrative of the post office being a niche job for African Americans. Many of my black co-workers, for example, had college degrees and were active in their community as well as at the workplace. Black civic engagement in the postal unions over the years had a lot to do with why the Great Postal Strike of 1970 was so successful. That rank-and-file “wildcat” strike produced the good salary, benefits, and union protection with full collective bargaining rights enjoyed by newly-hired postal workers like me ten years later.

I started as a Bulk Mail Center distribution clerk in Denver, Colorado in 1980, and then transferred that same year to letter carrier craft, where I stayed until my early retirement in 2000 in Durham, North Carolina, where my family and I had moved in 1988. I left the post office after being accepted by the history doctoral program at Duke University, whose East Campus was right across the street from my mail route. I “clocked out” of West Durham Post Office on a Friday in late August, and started classes the following Monday. With my main focus being on US, African American, and labor history, studying the black experience at the post office pulled those three areas together. It also became a lens through which I could examine the post office and its unions. But it was an important story in its own right—a narrative of struggle and activism with countless stories to read and hear about. There was William Harvey Carney, flag bearer for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, USCT in the Civil War, became the first vice president of the New Bedford NALC Branch 18 in 1890. And Minnie Cox, the Indianola, Mississippi postmaster forced out of office in 1902 after white mobs threatened her life.

I barely scratched the surface with my collection of stories like these spanning over a century. Unfortunately the story of African Americans at the post office has for the most part been neglected by scholars. But there have been notable exceptions, including the National Postal Museum, as well as historians working for the National Alliance of Postal and Federal Employees (NAPFE, formerly the NAPE) and the USPS. I hope those who are curious to learn more, or have stories of their own, will join us Saturday November 6th at the National Postal Museum to share these and other stories that have played key roles in the making of the modern post office!

About the Author

Philip F. Rubio is author of There's Always Work at the Post Office: African American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality. Rubio will speak at the museum on Saturday, November 6th at 1 p.m. ET. Watch the live webcast or view the recorded talk on the museum's YouTube page within a week after the lecture. Before and during the webcast, participate in the Q&A by tweeting questions @PostalMuseum