This text on this page is archived from the National Postal Museum exhibition Posted Aboard RMS Titanic, which ran from April 14 to October 30, 2001. It did not appear in Fire & Ice.

This text on this page is archived from the National Postal Museum exhibition Posted Aboard RMS Titanic, which ran from April 14 to October 30, 2001. It did not appear in Fire & Ice.

This video features the heroic story of the ship's mail clerks and ends with remarkable underwater footage of the ship.

[Music]

Narrator:

Titanic, completed in 1912 she was called a floating palace, the queen of the ocean, the largest most luxurious vessel of any kind ever constructed.

Designers and engineers spent three years and millions of dollars to ensure that the liner would offer passengers the very latest in speed, comfort, and safety.

The press raved about Titanic's design, declaring the liner superior to anything afloat and practically unsinkable.

Yet as most school children know, the great ship Titanic did sink, on her maiden voyage, after striking an iceberg in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

What is less well remembered today is that Titanic's full name was RMS Titanic.

"RMS" stood for Royal Mail Steamship, a prestigious title indicating the ship was legally commissioned by the British Monarchy and the US Government to carry mail.

In the case of Titanic that mail also carries with it continuing mystery.

Wednesday, April 10th, 1912, the Titanic set sail from Southampton, England.

On board, passengers enjoy the comforts of the world's most magnificent liner.

Meanwhile several decks below, five Sea Post clerks, three American and two British, are busy stowing sorting and processing hundreds of packages and more than 1,700 bags of mail.

Later that same day, April 10th, Titanic makes intermediate stops in Cherbourg, France and then Queenstown, Ireland where more passengers and mail are loaded.

Titanic finally departs for New York on the afternoon of April 11th, carrying 2,200 passengers and crew and, among its tons of cargo, more than 6,000,000 letters and packages.

Three nights later, Titanic strikes an iceberg and sinks killing 1,500 people including all five postal clerks on board.

The wreck of the Titanic was first discovered at the bottom of the icy Atlantic in September of 1985.

The pictures taken since then are a reminder of the human dimensions of this great tragedy.

But it's only in recent years that researchers from RMS Titanic Incorporated have been able to explore the more narrow interiors of the sunken ship, including for the first time the mailroom and post office.

The search team must first dive 2 and 1/4 miles, nearly four kilometers, in a submersible called Nautile.

Once they reach the Titanic site divers launch this smaller remote-controlled vehicle nicknamed Robin.

Robin first descends into one of Titanic's passenger decks and finds these light fixtures.

Next, Robin searches for a passageway down into Titanic's hull.

This bunker hatch, located near the bow of the ship, leads to a cargo shaft immediately adjacent to the mail room.

The hatch is found, and Robin goes inside.

As she passes through "D" Deck, Robin locates these bars which separated the cargo shaft from a third-class recreation area.

Further down the shaft, Robin arrives at "G" Deck - location of Titanic's post office.

On the left, and overturned table.

In back, these folding gates once separated Registered Mail from other mail.

Finally, Robin descends to the orlop deck, site of the mail storage and sorting room.

This mossy pink material, some unknown sea life growing on the canvas mailbags.

So, with the help of some extraordinary technology,

human beings have seen Titanic's mail rooms

for the first time in nearly ninety years.

Yet, 6,000,000 mysteries remain here.

What letters to loved ones, cherished photographs, or family heirlooms might still be resting here?

What lives were forever changed because this mail was never delivered?

Some questions, technology can never answer.

THE BEST OF THE BEST

Sea post clerks were highly skilled and respected postal workers who sorted, canceled and redistributed the mail in transit. Most were selected from the ranks of the Railway Mail Service or the Foreign Mail Section. Regarded as the best of the best, these men typically sorted more than 60,000 letters a day, making few errors. Their hard work and efficiency allowed the mail to be delivered immediately or forwarded directly to other destinations at the end of a voyage. Titanic had five sea post clerks aboard: three Americans and two British.

Oscar Scott Woody, a native of Roxboro, North Carolina and an ardent Freemason, had 15 years’ experience with the Railway Mail Service before joining the Sea Post Service.

At 48, John Starr March was the oldest of the American postal clerks assigned to Titanic and appeared to carry a curse of bad luck. During his eight-year career as a sea post clerk, his ships were involved in eight separate emergencies. His two adult daughters implored him to seek safer work after their mother died in June 1911, he had grown accustomed to the sea and was unwilling to give up his grand voyages.

William Logan Gwinn spent six years as a sorting clerk in the Foreign Mail Section before going to sea. He was originally assigned to sail on the American Line’s SS Philadelphia, but requested an earlier voyage upon learning that his wife Florence was gravely ill at home in Brooklyn. He was transferred to Titanic. Florence Gwinn recovered, but her family kept the news of Will’s death from her for many months.

Woody, March, and Gwinn worked alongside British clerks James Bertram Williamson and John Richard Jago Smith. Both Williamson and Smith were bachelors who financially supported their siblings and aging parents.

POSTAL LIFE ABOARD TITANIC

On April 9, 1912 March and Gwinn toured their new ship and found much to like. Titanic’s mail sorting room was far superior to any they had ever worked in before. Most mail sorting rooms of the time were far removed from where the mailbags were stored, often relegated to a cramped and poorly ventilated space. The mailbag storage compartment aboard Titanic, however, was conveniently located directly below the mail sorting room.

The mail clerks objected to their sleeping and meal arrangements among the third-class passengers, however, and secured alternate accommodations and permission to dine in a private area.

MOVING TITANIC’S MAIL

In all, 3,364 mailbags were brought aboard Titanic at three points — at its embarkation port at Southampton, England (1,758 bags); at Cherbourg, France (1,412 bags); and at Queenstown, Ireland (194 sacks) — before the ship headed for its final destination of New York City. Before sailing, the clerks carried out the routine tasks of checking the mail sacks and storing those that did not require their attention during the voyage. As Titanic set sail, the five postal workers began sorting the mail, distributing letters and packages into mailbags according to their final destination. Their goal was to dispatch Titanic’s mail immediately upon arrival at the Quarantine Station in New York Bay, where all incoming ships were detained for health inspection purposes.

THE MAILROOM BEGINS TO FLOOD

The five postal clerks were celebrating Oscar Scott Woody’s forty-fourth birthday in their private dining room when Titanic crashed into the iceberg. Realizing that something was terribly wrong, they rushed to the mail sorting room and found the starboard hold already beginning to flood. Beginning with the registered mail, they began hauling mail sacks to the upper decks. John Richard Jago Smith was dispatched to the bridge to report on conditions, but his report only confirmed what Captain Edward J. Smith already knew: Titanic was sinking.

Mail was considered a precious cargo. Steamship companies and the postal system went to great lengths to ensure its safety. Sea post clerks were expected to protect the mail at any cost. During Titanic’s sinking the five clerks onboard tried desperately to save the mail and, in the process, forfeited any chance they may have had to escape the doomed ship.

RECOVERED AT SEA

None of Titanic’s postal clerks survived the sinking. Only the bodies of Oscar Scott Woody and John Starr March were recovered from the wreck site. Due to its poor condition, Woody’s body was buried at sea. March’s remains were shipped home on May 3, 1912 and interred at Newark, New Jersey.

Rescuers made every attempt to properly identify the bodies recovered at sea following Titanic’s sinking. Each body was assigned a number as it was recovered, and a small effects bag stamped with that number was used to hold the personal items found on the body:

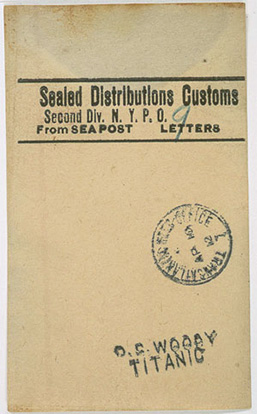

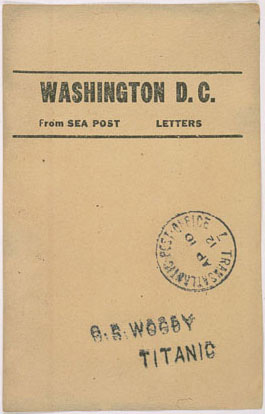

Oscar Scott Woody’s personal effects bag

Woody’s bag contained a “watch; fob; chain and clip; 2 fountain pens; letters; knife; cuff links; 1 gold ring; keys and chain; [and] $10.02.” March’s bag contained his gold watch and chain, as well as his ring with the initial “M.”

Oscar Scott Woody’s pocket knife

Courtesy Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Maryland.

Oscar Scott Woody’s pocket watch

Ingersoll pocket watch belonging to Oscar Scott Woody, corroded from immersion in sea water

Courtesy W. John Miottel, Jr.

John Starr March’s pocket watch

Pocket watch stopped at 1:27, found on John Starr March’s body when it was recovered at sea. It strongly suggests that the postal clerks survived the initial in-rush of water in the mail compartment around 11:40 p.m. and supports eyewitness accounts of survivors who stated that the mail clerks were actively attempting to rescue the mail until the absolute last moments before Titanic vanished.

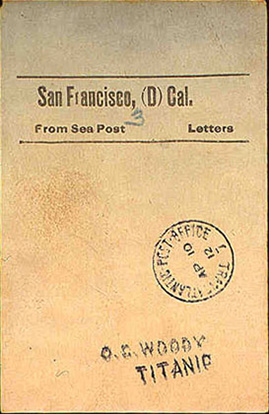

Facing slips

Also among the items in Oscar Scott Woody’s effects bag was a quantity of facing slips, used on top of mail bundles to indicate their destination. As required of all sea post clerks, Woody stamped his name on his slips so that any errors in distribution could specifically be charged to him. These facing slips were among those found on Oscar Scott Woody’s body when it was recovered at sea:

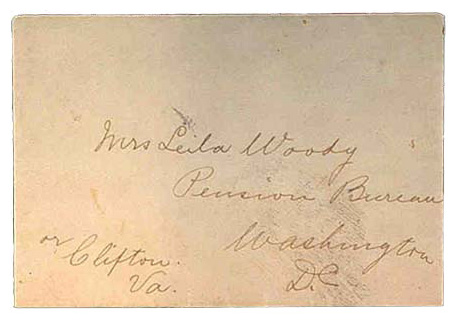

Notification card

Oscar Scott Woody’s wife, Leila, received this notification card officially informing her that her husband’s body had been recovered at sea and outlining how she could obtain his personal effects:

Courtesy Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Maryland.

Courtesy Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Maryland.

HOW MUCH MAIL WAS LOST?

While there is no way of knowing exactly how many letters were lost when Titanic sank, newspaper accounts at the time indicated that there were 200 registered mail sacks containing approximately 1.6 million pieces of mail, while the remaining 3,164 standard mailbags each held about 2,000 pieces of mail each. The entire loss was estimated between six and nine million pieces of mail and between 700 and 800 parcel post shipments.

CAN TITANIC’S MAIL BE DELIVERED?

The recovery of paper bank notes from the Titanic wreck site in 1987 raised the possibility that some of the ship’s mail may one day be salvaged. Letters and newspapers may have survived for a century in the dark and chilly waters of the North Atlantic.

The ‘sanctuary principle,’ endorsed by the Smithsonian Institution, embraces the hope that Titanic’swreck site will be preserved in undisturbed condition as a memorial to those who perished. Her mail, however, may be one exception to the sanctuary principle.

The delivery of mail is the obligation of the postal system to which it was entrusted. Should any mail sacks ever be salvaged, the Royal Mail or United States Postal Service could take steps to recover and deliver the mail. What to do with any mail that might be brought up from the ship is certain to raise many intricate legal questions. Distribution of Titanic’s mail a century after it sank would be extremely complicated and require a great deal of dead-letter detective work.