Unlike other printing methods, offset lithography (also called “lithography,” “litho,” or “offset”) does not involve cutting or etching a design into a plate. Instead, the image is imprinted on a smooth surface with a chemical. A second, water-base solution is wiped over the surface, filling in around the design. Ink applied to the surface is repelled by the water, sticking only to the design. A rubber blanket, fastened around a cylinder, then transfers the ink to paper.

Lithography produces softer images than engraving and is less secure, but it is cheaper and more efficient, with fast set-ups and less maintenance. Rubber surfaces are also more forgiving of paper variations. For these reasons, the United States used lithography for a few stamps at the end of World War I.

Modern stamp lithography is much sharper. It also uses process color, with separate plates for each color layer; each layer is made up of very fine dots. The first U.S. stamps printed entirely with full-color lithography appeared in the early 1990s. To ward off counterfeiters, lithographed stamps incorporate a variety of security features, such as those in the 1997 Air Force stamp.

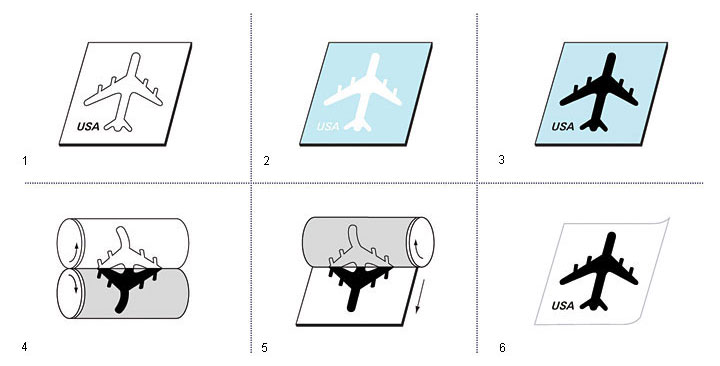

This simplified diagram shows the principle of offset lithography using one ink. Modern lithographed stamps normally use process color (multiple inks).

- 1) A design is imprinted on a smooth surface.

- 2) A water-base chemical fills the surface around the design.

- 3) Ink is applied; since it contains oil, it sticks only to the design.

- 4) A rubber blanket fastened to a cylinder picks up the ink.

- 5) The blanket transfers—or offsets—the ink to paper.

- 6) The inked image is complete.