When most people think of The Vermont Country Store, they think of the little red store in Weston Vermont, a cozy warren with creaky wooden floors and beams darkened by age; stocked with wool clothing, penny candy, old gaslight fixtures, nostalgic toys, and gadgets for country living. Most people assume the owner ran the store for decades before trying his hand at a catalog mailing.

In fact, the catalog was born a few months before the store, in late 1945. Both were the creations of Vrest Orton. Vrest’s grandfather, Melvin Teachout, and father, Gardner Lyman Orton, operated a general store in the tiny village of North Calais, Vermont, from 1896 to 1910. Vrest grew up in the store, stocking shelves, stoking the woodstove, trimming the wicks on the kerosene lamps, and listening to customers telling stories of the Civil War. From his earliest days, Vrest saw the country store as community center and a place where history lived.

But rural country stores had been in decline since the early 1900s, thanks to the automobile. In the 1890s when horse-drawn buggies were still common on country roads, a shopping trip to a town 20 miles away was a day’s work. By 1940, when 50% of American households owned a car, a shopping trip was a few hours’ recreation. Small cities had thriving downtowns filled with specialty shops and soda fountains and movie theaters, all catering to Saturday crowds. Larger cities had department stores. Tucked into a rural village and stocked with a bit of this and a bit of that, the little country stores no longer seemed necessary, and by the 1940s they were nearly extinct.

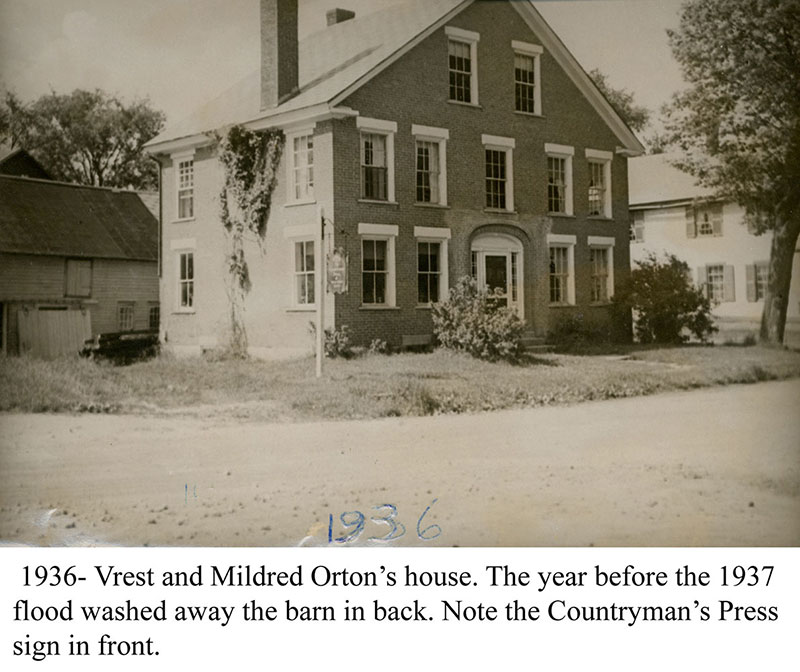

Vrest became a writer, working in advertising in Los Angles and writing for The American Mercury magazine in New York under the renowned H. L. Mencken. He returned to Vermont in 1933 to write for Tuttle Publishing Company in Rutland, where he met his wife-to-be Mildred. He also ran his own publishing company, Countryman Press, often operating the press himself. When WWII broke out, Vrest and Mildred moved to Washington to work for the Pentagon. At end of the war, Vrest’s colleagues went back to careers in publishing or advertising, but he had been nursing an idea: to recreate the lost country stores of his youth. He had lived in the Vermont village of Weston and been involved in its revival efforts; now it occurred to him that “To add an old-fashioned, authentic, operating rural country store to this picture was an exciting and beckoning prospect.”

Vrest Orton travelled around Vermont collecting countertops, glass display cases and light fixtures from half a dozen abandoned country stores. His first stop was his father’s former store in North Calais. The store was gone—in fact, most of the village was gone, sunk into cellar holes—but some of the fixtures had been sold to another store nearby and he was able to recover them. He found a building in Weston Vermont that bore an “uncanny resemblance” to the North Calais store, spent the fall of 1945 outfitting it, and opened early in 1946.

By then, Vrest had already produced the first The Vermont Country Store catalog. It was a very modest effort—just 12 letter-sized pages, printed with hand-set type on a Peerless press and assembled on the dining room table. It mailed in December 1945. The mailing list —about 1000 people—was modest too; it was essentially the Orton’s Christmas card list. But it contained all the elements that The Vermont Country Store catalog would become famous for: quirky products, no-frills black-and-white photography or pencil illustrations, and Vrest’s distinctive writing style, honed through years of advertising and editorial writing. The first item in the catalog is a sewing chest:

Sewing Chest

I want to tell you about Baird and Steven Hall who live down the road from my place a piece. Baird makes things of good Vermont pine and Steven decorates them by hand…

Those early catalogs had to work hard, because the business model itself was still a novelty. There were a few well-established mail-order companies like Sears (1888) and Orvis (1856)—the latter located in nearby Manchester, Vermont. But for most people, the notion of putting money in an envelope and sending it to an unknown company in the hope of receiving goods by return mail was foreign. In each catalog, Vrest invested a paragraph or two to give hesitant customers his personal reassurance, fortified by his distinctive guarantee, “The Customer Bill of Rights.”

The Vermont Country Store was intended as a kind of working museum, a place where customers could get a look back in time to a simpler, more rural America; but also where they could buy useful, reliable products, especially specialty products from the past.

The same is true of the catalog, perhaps even more so. Vrest’s son Lyman (who grew up learning the art of storekeeping and took over the business in 1975) put it this way:

“The more I look at other catalogs, the prouder I am of what we do here. Mail order companies like to compete for your attention by offering the most outlandish product they can find. But it’s plain that what sensible people really want are the kinds of practical goods that have been our stock in trade since 1946. We’re a real country general store, filled with good, honest, useful merchandise needed by country and city people alike.”

Offering these kinds of sensible, old-fashioned specialty products is only possible because of the postal delivery system. Even in a mid-sized city, there aren’t enough customers for a manual typewriter—let alone replacement ribbons—to make it worth a store’s while to carry them. But the Vermont Country Store has them, as well as wall-mounted phones, vinegar tonic, Tangee lipstick, watermelon pickles, and its own line of flannel pajamas. That first catalog even sold gourmet popcorn, a commodity today but hard to find at the time, using Vrest’s personable, take-your-time writing style. The entire ad runs:

Vermont Bearpaw Popcorn

More and more folks are taking to popcorn, not only as a snack, but as a supper meal with milk, or indeed, as a confection. When I was away in Washington these last 3 years I thought I’d never stand it until I got back to Vermont where I could pop some old-fashioned Bearpaw in my iron kettle and have a good meal. (Also there are lots of vitamins in popcorn).

But I found popcorn almost impossible to get. The dealers haven’t got any Bearpaw. I looked for weeks and at last, lucky for me, I found Fred Abbey who had sense enough last year to raise about 15 acres of the genuine Vermont Bearpaw (so-called because the cob is shaped like a bear’s paw).

It pops fluffy, light, white…and tender! The flavor is the best I have ever tasted, and I am a crabby fellow who insists on something pretty special in popcorn. I can do without meat, but I have got to have my popcorn three times a week!

I’m glad I can share some of this Bearpaw with you…when it’s gone there won’t be any until Fred’s crop is next cured. Case of 4 lbs. is $1.00

It’s not hard to see why Vrest’s copy has become legendary in the world of direct mail advertising.

The Vermont Country Store is proud of its heritage as an old-fashioned catalog. Vrest wrote:

Some bright morning the mailman may hand you an unusual and surprising kind of mail-order catalog. You may well mistake it for a New England Almanac of 1888.

You might make the same mistake today. The catalog was, remarkably, printed entirely in black and white until 2002. Some products were photographed, but just as many were depicted only in pencil or ink illustrations. Occasional spots of color were introduced in 2003. In 2007, the same year Apple introduced the iPhone, the Vermont Country Store Catalog finally graduated to full color. The company has a website, but still derives the majority of its business from the catalog.

The company adopted a wait-and-see attitude about new list management and mailing technology, too. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the company thrived thanks to Lyman’s mail order savvy and his knack for finding unusual products; yet during this mail-order boom customer records were still kept on 3 x 5” cards. “We guarded those cards with our lives,” says Lyman.

Being slow to adopt the latest look is not a gimmick. It is a reflection of two things. One is frugality and the old Yankee attitude that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” The other is sympathy for the fact that, for many customers, the world is moving too fast and there is too much frenetic visual stimulation. When The Vermont Country Store catalog arrives in the mailbox, it is an invitation to slow down a bit and take it easy. Customers accept that invitation, settling in for a good read and often sending handwritten notes along with their mailed orders. These are customers who have a letter-writing desk, a collection of notecards, and a book of stamps.

Unlike modern-styled catalogs with their full-page images and large swaths of white space, The Vermont Country Store catalog is densely packed, with 8 or more items on a page. This helps re-create the delightfully cluttered look of the store, where there are opportunities for discovery. Something unexpected—even, sometimes, unrelated to other products—might be found on any page. High density also enables the company to sell low-priced items in spite of the rising costs of paper, postage, and shipping.

The copy is not as perambulating as Vrest’s original writing, but it is long by today’s standards, and full of information. There are no clever modernisms or plays on words, and the copy is never shrill. As Vrest was fond of telling Lyman, “Don’t try to sell too hard. Just explain the merchandise and people will buy it if they need it.”

That’s the philosophy that prevails today. Lyman’s sons Cabot, Gardner, and Eliot are the fifth generation of storekeepers, guiding The Vermont Country Store to sure-and-steady growth. The company has been featured on NBC Nightly News, The Martha Stewart Show, NBC with Mike Leonard, CBS This Morning, and The New York Times. More importantly, it serves millions of customers in town and country, in every state of the union. As long as they can find useful products no one else offers, and as long as a way exists to deliver catalogs and packages to customers, the Orton family will keep at it.